Book Review: Expectations Investing

Michael Mauboussin and Al Rappaport's Expectations Investing has immediately become one of the most influential books I have read. I regularly refer back to it as a resource for clear and concise explanations of some of the most foundational topics in investing.

Everyone reads investing books hoping to take away a nugget or two to apply to their own process, but this book is, from cover to cover, a handbook on how to assess businesses and understand value creation with literal step-by-step instructions.

The book introduces the expectations investing framework, which advocates that "stock prices are the clearest and most reliable signal of the market's expectations about a company's future financial performance."

Instead of projecting a company's cash flows and discounting them back to today, expectations investing starts with the current stock price and solves for the expectations implied by the price. Then you compare those "price implied expectations" with your own.

If your expectations outstrip what you believe is priced in, it's reasonable to anticipate that the market's expectations will eventually be revised upwards to meet that reality in the future, and the price should follow.

Differences in expectations between you and the market are only likely to be meaningful on a few metrics. Overwhelmingly the key metric is sales, driven by either volume or price/mix. The other "value triggers," as he refers to them, are operating costs and investments, which are ultimately reflected in a different free cash flow margin. So the bulk of the analysis, after setting up the fairly straightforward but consciously imprecise reverse DCF, is in figuring out your expectations for metrics like unit sales and assessing their likelihood vs. those implied by the market.

In order to be confident that you are comparing expectations apples-to-apples with the market, you need to make some sound assumptions about things like the discount rate and the way that you arrive at free cash flow. At a more base level, however, you need to truly believe that the value of a company is based on its future cash flows discounted to the present. It's never been easier to outright reject that notion looking at some of the current market activity and asset prices. Many investors talk in these terms but ultimately base their decisions on intuition, momentum, multiples, and fear of missing out.

Mauboussin goes to great lengths to dispel several common misconceptions and ground us in the truth that stock prices reflect long-term cash flow expectations. In fact, there is a whole chapter called How the Market Values Stocks. In it, he quotes John Bogle:

"Sooner or later, the rewards of investing must be based on future cash flows. The purpose of any stock market, after all, is simply to provide liquidity for stocks in return for the promise of future cash flows, enabling investors to realize the present value of a future stream of income at any time."

He explains that higher portfolio turnover and large moves in share price around quarterly earnings releases are often used as evidence that investor time horizons are short-term. However, those movements are a result of shifting expectations about long-term performance based on new information. Average holding periods are different from the market's investment time horizon. One of the calculations made in the expectations investing process is the "implied forecasting period," or the number of cash-flow-generating years required to justify the current share price. The market average is over 10. "investors make short-term bets on long-term outcomes," he says.

Mauboussin's recent paper, Everything is a DCF Model, makes similar assertions, imploring investors to realize that, even when they use multiples as valuation shorthand, cash-generating assets are valued based on the DCF.

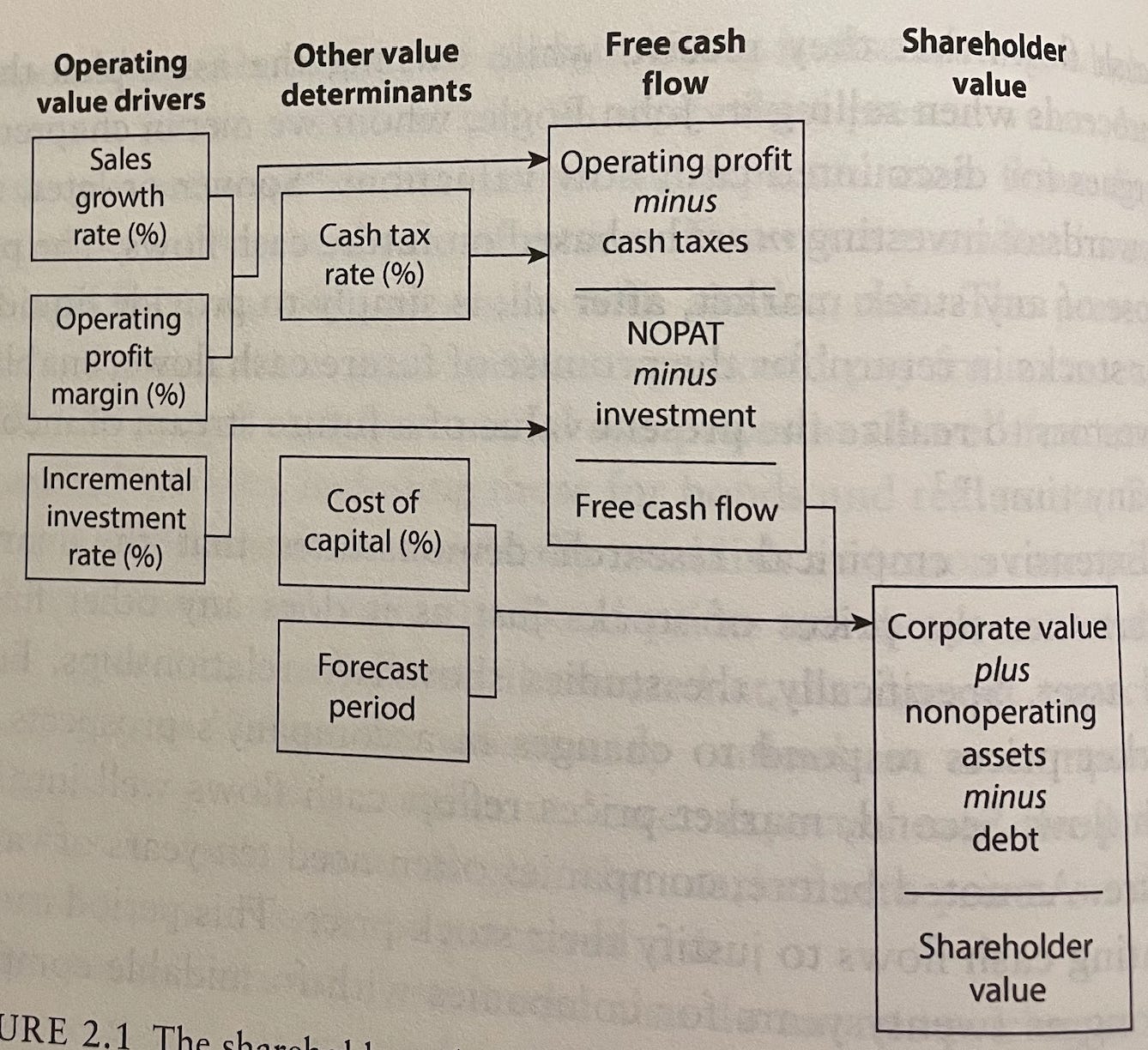

I found that this flow chart, along with several others like it, radically simplifies the concept of value creation. Free cash flow is the operating profit, determined by sales minus operating expenses and cash taxes, minus the incremental reinvestment needs of the business. That number discounted back to today over the forecast period is the root of your valuation.

The premise of the book is so simple that it can be adequately explained in the first few chapters, and the rest of the book serves as a how-to guide on identifying opportunities for revisions in expectations, which metrics, if revised, are likely to result in the largest changes in value, and what to do with companies like Amazon, who seem to have a large amount of optionality priced into shares that can't be accounted for in a regular DCF. I expect to keep learning from and referring to this book for some time - it will stay on my desk, not on the bookshelf.